Exploring the Hidden: Part 2

Esther, Purim and a Fresh Take on the Role of Jewish Women

In Part 1 of “Exploring the Hidden,” we examined our Western ethnocentric lens as a barrier to appreciating the role of women in Judaism. Contrasting values (specifically vis a vis the public versus private domain and the role of the physical and spiritual in our lives) create disenchantment. In Part 11, we continue the exploration with a focus on the Hidden Queen – Esther and the story of Purim.

To return to Esther (the exemplar of womanhood) and Purim (the ultimate accomplishment of concealment,) we find there too the supremacy of the physical. The commandments of the festival are connected with the most physical aspects of our lives. We are obligated to eat a special Purim meal, to send packages of food to friends and gifts to the poor. Furthermore, the Talmud says that on Purim we are obligated to drink to the extent that we no longer know the difference between “cursed is Haman” and “blessed is Mordechai.” The reason for the emphasis on physical activity on Purim is a direct result of its transcendent concerns. Our rabbis teach that Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, can be read as Yom KePurim, a day which is like Purim. We tend to think of these holidays as being diametrically opposed. The former is a day of asceticism devoted to prayer and spirituality. The latter is a festival of merriment and physical satiation. Yet not only are the two compared but Yom Kippur is like Purim. Purim is the yardstick, the epitome of holiness. This is so because spirituality which must still renounce physicality is limited. G-d is beyond the limitations of finite and infinite and the greatest evidence of His transcendence is that His essence is to be found in the physical.

In Jewish eyes, to associate women with the body and the material world, to celebrate Purim in the most physical of ways, is not a denigration but an acknowledgement of sublimity.

One may still assert that although in the Messianic era, “the soul will take life from the body”, at present, the soul is still higher. The relationship is one of flux. And flow of influence is a lesson for personal growth.

In the Messianic era, the soul will take life from the body.”

Giving and Receiving

The modes of giving and receiving are embodies in the sefirot, (spheres of progressive emanation of Divinity) as represented by the Kabbalistic tree of life. The lowest and last of these levels is the sphere of malchut which, as mentioned earlier, is associated with women and the physical world. Albeit the lowest, its source is the highest, beyond even the beginning of emanation. As the verse states, “the last in creation was the first in His thoughts.” The Zohar teaches that malchut “has nothing of its own.” It merely receives from the upper sefirot as the moon reflects the light of the sun. Yet in this absence of any independent existence, it parallels the true nothingness of G-d. It is through receiving that malchut becomes elevated to its source above the sefirot of prior influence.

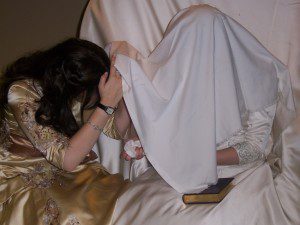

Malchut then also embodies the concept of bitul, nullification. It is only when we enact self-nullification and surrender ourselves to our Creator that we can reveal our source beyond creation and become truly active beings. Unity occurs when both giver and receiver are ready to assume their roles. The Zohar says that precisely through the union of Male and Female, the essence is revealed. Birth and creation arise out of bitul and receiving.

This transformation from receiver to giver is most clearly seen in two opposite perspectives of Shabbat. On the one hand, our sages have stated that “whoever prepares before Shabbat will eat on Shabbat.” Being that Shabbat is the last day of the week, it is perceived as receiving from the prior six days. Elsewhere it is stated that “all the days of the week are blessed by Shabbat.” Implicit here is the idea that Shabbat is the source and origin of all influence. The apparent contradiction is resolved in understanding that Shabbat too is associated with malchut. Because on Shabbat, malchut is elevated to its source. The receiver becomes the giver. Just as the week as a preparation for Shabbat, at which point it receives from Her, so too, is the exile a preparation for the final redemption at which time we will be able to point to G-dliness and true nature of existence as we now do at ourselves and the objects of our reality. At that time, we will witness the revelation of the supernal root of not only malchut and women, but their associated constructs too. Albeit that women are stereotypically seen as embodying kindness, and men as embodying strength and sternness, according to Kabbala the opposite is true. In addition to malchut, women are also associated with the sefira of gevurah/strength, and men with that of chesed/kindness. So too do the Levites and the House of Shammai have their source in gevurah. In the Messianic era, not only will the soul take life from the body, but Levites will be priests, the authority of Hillel will give way to Shammai, and Isaac will emerge to the fore as malchut is elevated to its source.

The duality between giver and receiver is to be found also in the leitmotif of Purim. Although Esther’s name means concealment, the book we read on Purim is called the megillah which means revelation. The contradiction is only apparent, for in these terms, it is given prior concealment that revelation must occur.

The predominant private role of Jewish women and the association with malchut and physicality of Jewish women not only indicate their elevated status in Torah thinking. Their implications of humility and nullification direct and open the way to a realization of our true selves.

This article originally appeared in Wellsprings Magazine